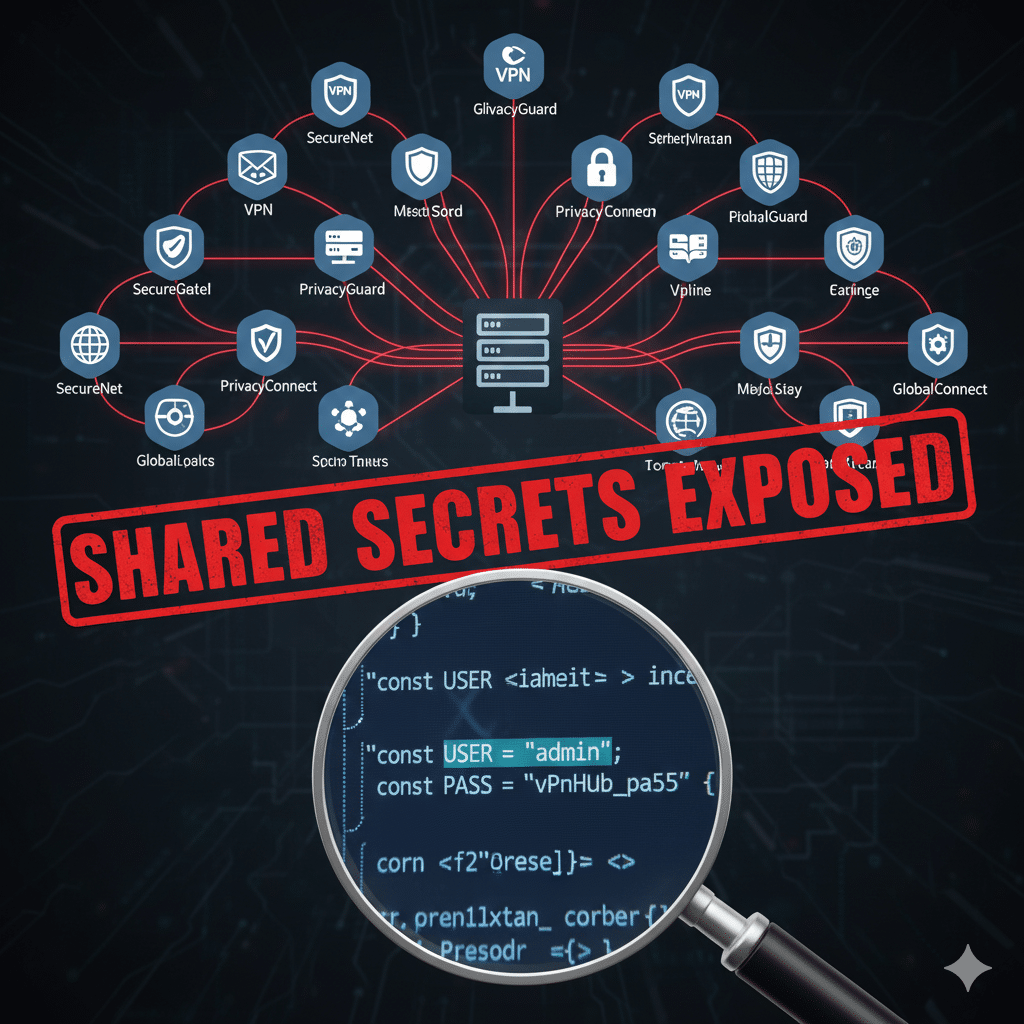

A new academic and industry investigation has exposed a surprising — and alarming — reality: more than 20 widely-downloaded Android VPN apps (collectively exceeding 700 million installs) belong to a few hidden “families,” share infrastructure and code, and in many cases embed the same hard-coded credentials (VPN-app networks). That combination of opaque ownership and shared secrets can let attackers decrypt traffic, impersonate servers, or perform on-path interception — turning tools marketed as privacy defenders into systemic privacy risks.

What the research found

Researchers applied business-records analysis, APK reverse engineering, and dynamic testing to link seemingly independent VPN brands into three interlinked families. They discovered recurring, reused Shadowsocks passwords and other shared cryptographic material hard-coded inside application packages — effectively creating identical keys across many distinct apps and servers. Because Shadowsocks lacks built-in asymmetric key exchange, reusing or hard-coding passwords makes traffic decryptable if an attacker obtains the shared secret. The paper documents how these insecure practices enable decryption and blind on-path attacks, especially over public Wi-Fi. (

Key findings reported by multiple outlets include:

Over 20 apps mapped to three families with shared servers, code, and credentials.

Combined installs exceed 700 million on Google Play.

Hard-coded Shadowsocks credentials and deprecated ciphers were found, undermining encryption promises.

These are not isolated coding mistakes — they reflect systemic issues in the development, supply chain, and vetting of consumer VPN apps.

Why shared credentials matter

VPNs promise confidentiality by encrypting user traffic between the device and the VPN server. That security depends on secret keys and proper key exchange. When apps embed identical credentials or use weak/deprecated ciphers:

Anyone who extracts the shared password (from an APK or leaked server config) can derive symmetric keys and decrypt traffic from any user using that family of apps.

Reused credentials increase attack surface — compromising one server or app variant compromises many users across brands.

App store vetting fails to catch ownership links — store listings can make different apps appear independent while they rely on the same backend, misleading users about choice and trust.

Put simply: shared secrets + opaque ownership = system-level fragility for millions of users.

Real-world implications

For end users, the most immediate threats are credential theft, traffic interception, and loss of anonymity. On public Wi-Fi or compromised networks, an attacker who gains access to the shared credential can mount man-in-the-middle attacks and read otherwise “encrypted” traffic. For enterprises, employee devices running such consumer VPNs risk becoming entry points into corporate networks under BYOD policies. The research prompted warnings from security teams and coverage across tech outlets, urging users to reconsider which VPNs they trust.

How this slipped through app stores and what should change

The papers and follow-up analyses pin responsibility across several layers:

Developers shipping hard-coded credentials or relying on insecure protocols.

App marketplaces failing to detect common server endpoints or shared binary artifacts that indicate linkage.

Security reviewers understating supply-chain risks for free/ad-supported VPNs.

Researchers recommend stronger developer identity verification, mandatory third-party security audits for privacy apps, and automated scanning for hard-coded secrets in uploaded binaries. They also suggest discouraging or warning users about Shadowsocks use in consumer apps unless secure secret distribution is implemented.

Practical advice for users and organizations

Avoid obscure, free VPN apps. Reputation matters. Prefer vendors with public company records, audits, and modern protocols (WireGuard/OpenVPN with proper key exchange).

Check for third-party audits and transparency reports. Legitimate VPN providers publish audit reports and have clear ownership and contact details.

For BYOD policies, enforce corporate whitelists. Block unknown consumer VPN apps on corporate devices; require approved enterprise VPN or ZTNA solutions.

Use network-level protections (HTTPS, multi-factor authentication) — do not rely solely on a VPN for end-to-end security.

Conclusion

The discovery that 20+ popular VPN apps are covertly connected and sometimes share hard-coded cryptographic credentials is a sharp reminder: not all VPNs are equally trustworthy. For millions of users the assumption of privacy may be false — the same underlying secrets and code can make supposedly independent VPNs trivially vulnerable to decryption and surveillance. The fix is multi-pronged: better developer practices, stronger app-store vetting, mandatory audits for privacy tools, and user caution when choosing a VPN. Until the ecosystem fixes these supply-chain and transparency problems, users should treat free VPN brands with skepticism and prefer providers with demonstrable security hygiene.